By Lee Levine and Stephen Wermiel

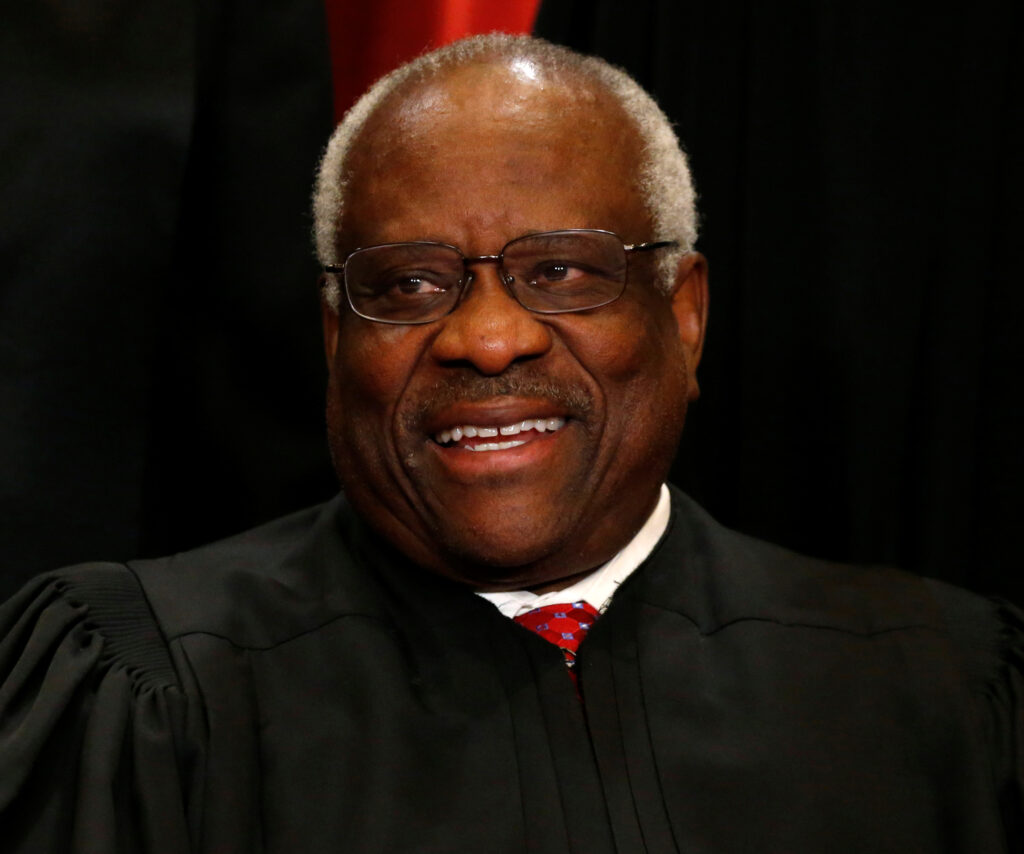

There are any number of obvious responses to Justice Clarence Thomas’s misguided assertion in McKee v. Cosby (2019) that New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) ought to be overruled. They include the overwhelming academic consensus applauding the decision both at the time and thereafter; the proper role of original intent in free speech analysis; the history of seditious libel in the United States and its dispositive significance in divining that intent in Sullivan; and the case’s place in defining “the central meaning of the First Amendment” that has guided the Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence for more than half a century. We explore all of them in a forthcoming extended essay in Communications Lawyer. Here, we focus on Justice Thomas’s dubious reliance on “original intent” as well as the curious timing of his assault on Sullivan.

Original Intent: Preliminary Points

Let’s begin with “original intent.” Neither Sullivan, nor any of its progeny, Justice Thomas asserts, “made a sustained effort to ground their holdings in the Constitution’s original meaning.” First of all, these words simply cannot be squared with Justice William J. Brennan’s opinion in Sullivan, four full pages of which are devoted to the Framers’ intent as gleaned from the most analogous historical experience—the controversy surrounding the Sedition Act of 1798. The Court not only traced this history at length in Sullivan, Justice Brennan also canvassed authoritative assessments of its constitutional significance, all of which, including most especially the published views of Justices Holmes, Brandeis and Jackson, reflected “a broad consensus that the Act, because of the restraint it imposed upon criticism of government and public officials, was inconsistent with the First Amendment.” This consensus—reflecting the considered judgment of “the court of history”—was and remains especially significant because, as Justice Brennan also noted, “the Sedition Act was never tested” in the Supreme Court.

Justice Thomas rejects both this consensus and the historical record on which it is based, largely on the grounds that (1) the common law of libel continued to exist without constitutional challenge following the controversy surrounding the Sedition Act and (2) several Justices noted, in the years before Sullivan, that “libel” was not protected by the First Amendment. None of this is surprising, or particularly persuasive, however, especially since the First Amendment was not held to be applicable to the States until 1925, Sullivan was the first case thereafter in which the Court undertook to assess the application of the common law in a manner analogous to the law of seditious libel, and none of the judicial statements that Thomas quotes therefore purported to speak to that issue.

Two More Points

Two other points are worth noting when assessing Justice Thomas’s professed allegiance to original intent. First, missing from his own discussion is any reference to the John Peter Zenger seditious libel trial in 1735. It is well accepted that the Zenger prosecution was a significant factor in solidifying the Colonies’ antipathy toward the Crown that ultimately led to the Revolution as well as the new nation’s insistence on a Bill of Rights that guaranteed its citizens the freedom of speech and of the press. One would have thought that the dramatic example of the Zenger trial, which had “set the colonies afire for its example of a jury refusing to convict a defendant of seditious libel against Crown authorities,” would be worth a mention in Thomas’s assessment of the historical record, especially since the quoted language in this sentence was written by him in his concurring opinion in McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission (1995).

Second, it cannot be seriously questioned that Thomas’s narrow focus on “original intent” is of limited utility in interpreting the First Amendment. Almost nothing in our First Amendment jurisprudence, including decisions Justice Thomas has written and joined, has turned on what the freedom of speech meant to the Framers. To cite just one example, it is difficult to imagine that the Framers believed the First Amendment restricted the ability of local governments to enact ordinances regulating outdoor signs displaying non-political messages, yet Justice Thomas had no difficulty writing an opinion for the Court holding just that in Reed v. Town of Gilbert (2015).

Trusting the States?

Beyond all this, there is the matter of Thomas’s curious assertion that the “States are perfectly capable of striking an acceptable balance between encouraging robust public discourse and providing a meaningful remedy for reputational harm.” Simply put, precisely the opposite was the case when the Court decided Sullivan and there is every reason to believe that, but for Sullivan and its progeny, an analogous effort by public figures to weaponize the law of defamation would be equally successful today.

As Anthony Lewis recounts in Make No Law (1991), his seminal work on the case, Sullivan’s suit, several others filed against The Times based on the same advertisement, and still others filed against other national media outlets then attempting to cover the civil rights movement were not motivated by a desire to recover damages for actual reputational harm so much as to dissuade the press from reporting to the nation about a subject of palpable public concern. The damage awards sought (and in many cases awarded) in multiple lawsuits aimed to make it too expensive for newspapers and television networks to continue reporting about civil rights. As Justice Brennan wrote in Sullivan, “the pall of fear and timidity imposed upon those who would give voice to public criticism is an atmosphere in which the First Amendment freedoms cannot survive.”

This Moment in History

It is against this backdrop that, after more than a quarter century on the Court, Justice Thomas chose this moment in our history to urge that Sullivan be overruled. He writes at a time when the President of the United States has dubbed critics of his official conduct “enemies of the people” and has called for the libel laws to be “opened up” in the manner Justice Thomas has now endorsed. He writes at a time when an unprecedented number of public officials and powerful public figures have brought defamation actions against national media and smaller publishers alike. Make no mistake, but for Sullivan and its progeny, such lawsuits would—as Brennan wrote in Sullivan—deter “critics of official conduct . . . from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and even though it is, in fact, true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court or fear of the expense of having to do so.”

What was true in 1964 remains true today: the libel law regime that Justice Thomas apparently favors “dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate” and is, for that reason above all others, demonstrably “inconsistent with the First and Fourteenth Amendments.”

This essay is being posted simultaneously on First Amendment News.

Tags