Colorado resident and self-described “First Amendment auditor” Chris Cordova sued multiple police officers from two separate departments, claiming he was retaliated against for exercising his First Amendment right to record police.

Cordova’s “Denver Metro Audits” YouTube channel has nearly 236,000 subscribers, and it is described as “a civil liberties and First Amendment auditing channel committed to defending your constitutional rights through accountability, transparency, and peaceful activism.”

One lawsuit, filed Aug. 22 in Colorado state court, claims two Englewood Police officers have “disdain” for Cordova’s actions as a First Amendment auditor, alleging one officer intentionally harmed him by hitting his hand with the cruiser’s door, and another allegedly submitted an arrest warrant affidavit which “contained false and misleading information.”

The second lawsuit, filed Sept. 1 in the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado, claims three Colorado Springs Police officers retaliated against Cordova by arresting him for interference, a charge for which a jury later found him not guilty. The suit also alleges that the City of Colorado Springs, the municipality of the police department, has an “official policy that singles out First Amendment Auditors for special treatment if they are being arrested.”

The Colorado Springs Police Department communications specialist declined to comment on the case.

In an official statement to First Amendment Watch, the Englewood Police Department said “As this matter involves pending litigation, the city cannot comment on the allegations or discuss the case in detail. The city is committed to following the judicial process and will respond through the appropriate legal channels.”

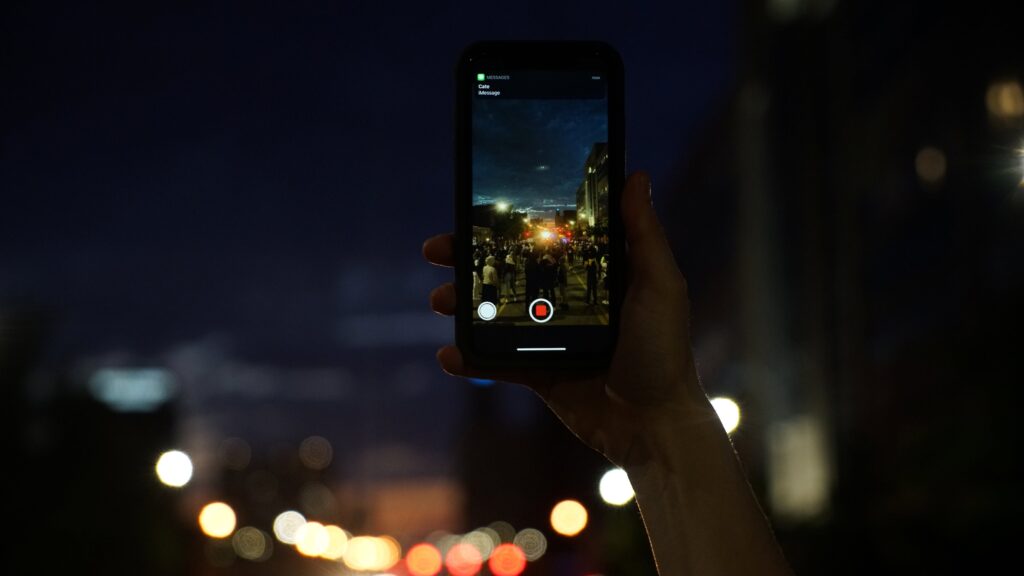

First Amendment auditors are individuals who specifically film on public property and police stations to test the rights to film in public spaces, and often aim to oversee the actions of public officials. Many audits are non-violent and uneventful. But some encounters have escalated dramatically, resulting in arrest and litigation.

(See our teacher guide on the right to record police or the more concise citizen’s guide to recording the police. Watch our in-depth video: “Recording Police: Know Your Rights”)

Seventy-six percent of the U.S. population lives in states where federal appeals courts have recognized a First Amendment right to record police officers performing their official duties in public, but the Supreme Court has not ruled on the issue.

Colorado residents have enjoyed the protection to record since 2022, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit held in Irizarry v. Yehia that the plaintiff’s “right to film police falls squarely within the First Amendment’s core purposes to protect free and robust discussion of public affairs, hold government officials accountable, and check abuse of power.”

First Amendment Watch spoke with Milo Schwab, Cordova’s attorney, about the two lawsuits. Schwab discussed the common goals of First Amendment auditors, the right to record police in Colorado, and what constitutes reasonable time, place and manner restrictions.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

FAW: Why does Cordova consider himself a “First Amendment auditor”? Is he trying to hold police accountable?

Schwab: I actually interact with a few of them, and a lot of their interests are different, but I would say there’s a very common theme running throughout, which is government accountability. What’s interesting is that the politics of it actually are not as straightforward as you would think. A lot of people, I think, might expect or assume that it’s going to be very liberal people, and that’s not always the case. In fact, I would say there are more conservative people that are engaged in First Amendment auditing than liberal people, and there’s very much a libertarian strain running throughout. Some people look at it as government resources, and we should be able to audit and record public officials, regardless of what they do, whenever they’re being paid by the people. That the work that they do should be able to be recorded, so that as a people we can watch over them and there is a record of that. That can run the gamut from police officers down to a social security agent, with the idea that if these government officers are being paid by the people, not everyone can always make sure that they’re doing good work, because there can’t be someone sitting in there. But if they’re being recorded or livestreamed, that can create a higher level of accountability. And that’s my observation. I wouldn’t necessarily ascribe that to any particular person.

FAW: In the September lawsuit, it states that Cordova was “15 feet from the ambulance, 5 feet from any officers, and 20 feet away from any individual involved.” This goes to whether the police were enforcing reasonable time, place or manner regulations. What were the emergency circumstances? And why were these distances reasonable under the circumstances?

Schwab: In these types of scenarios, I actually think the better way to look at these cases is through the First Amendment retaliation lens but the recording is interesting. I think that this is an area of the First Amendment that is actually a little underdeveloped, and we have been [reviewing] traditional protest and speech cases in a way that doesn’t necessarily fit neatly with the concerns, but also there are differences between saying something and recording something. Standing quietly and recording is just a different act, and it’s in some ways less disruptive. And that’s where, I think, I can see there being an additional push in the future through some enterprising First Amendment lawyer to say that the act of recording needs to be evaluated differently in, for example, a non-public forum. And that’s not to say that those restrictions aren’t reasonable, but the concerns are just different. Because there’s not the same disruptive concern, but there may be a greater concern over confidential information. Now, in this case, what I would say is, by silently standing and filming someone, the restrictions on that are generally not going to be reasonable, because they’re not interfering. There’s no objective that the officers are trying to achieve. And in this case, they said, “Go stand behind the ambulance.” Well, if you stand behind the ambulance, now there’s no alternative channel. [For time, place and manner restrictions to be valid, there must be ample alternatives for communication available.] The alternative channels they’re offering aren’t really appropriate, because now you actually can’t record the police if you’re being told to stand in a place [where you can’t see the police] interaction. There’s always going to be a very specific analysis. In this case, I believe it was someone that had been punched and maybe had a cut over their eye. They weren’t stabbed, they weren’t bleeding. They weren’t taken away in the ambulance. They just received a little bit of medical treatment. And whether or not most people would agree with, or even understand, the reason why Chris and others wanted to record this, the actual concerns that would lead to a time, place, manner restriction, at least in that crime, they’re pretty low. It’s more about police officers just not liking to deal with people being around in public, more than a legitimate concern that these people’s presence or their actions in videotaping is causing an issue.

But the additional issue here is actually something we have noticed in Colorado, and I know from the City of Houston v. Hill case, it’s probably a national issue. It’s an important Supreme Court case relating to free speech and criminal law. I have seen at least a dozen instances where someone who is recording is charged with obstruction, and at least in Colorado, and I believe the Hill case, requires that obstruction has to be something more than just being present or just filming. It has to be a physical act that actually hinders. Not even just the hindrance that is the criminal act. It is something wrongful that hinders, and just because you’re present filming an officer and that makes them divert their attention away, that is not, in itself, appropriate to be charged with a criminal charge, and that is what we see over and over and over again. And we’ve won. Unfortunately, we’ve had to defend many people filming police officers over and over and over again in Colorado on obstruction or interference charges, because officers will just say, “Well, their presence diverted my attention. We had to have an additional cover officer.” And yes, that could be true, but that’s always going to be true when you’re operating in public. And certainly if officers feel the need to bring in additional people to watch someone who’s filming, then that itself is enough, and we can’t actually have filming interactions between police and individuals in public.

FAW: Cordova has a First Amendment right to record police in the Tenth Circuit. But qualified immunity most often protects officers from liability when they are sued for violating this right. Have the First Amendment protections been widely established enough in Colorado and the Tenth Circuit to get around the qualified immunity for the officers?

Schwab: In the case Irizarry v. Yehia, it’s clearly established that they have a right to film police officers. There’s always going to be evaluations [to that type of case law], which is why we often still bring these in state court, because I would rather stay away from qualified immunity. There’s just an idiosyncratic nature to qualified immunity as well, depending on the judge you get. But I know that across the country, I believe it’s every odd circuit plus the Tenth, now recognizes the right to film police officers. And I believe the First Circuit opinion is actually a really good one. And it talks about not just the ability to film police officers, but I think it’s a little broader about filming not just police officers, but public officers in public and the need for that. But I’m not generally worried about qualified immunity. But proximity is an important question, not just to being able to see, but also being able to hear the interaction. And that is an important component.

FAW: So you don’t expect to run into any issues regarding qualified immunity in the federal case filed against police officers from the Colorado Springs Police Department?

Schwab: Neither case is going to raise any qualified immunity issues, because in the federal case, we didn’t bring a 1983 claim against any of the individual officers. We only brought a 1983 claim against the city, because that’s the only way we could. And cities are not entitled to qualified immunity. And we did it based on a policy because we captured the officers talking about an email that said, “For First Amendment auditors, you have to bring them to headquarters to fingerprint them.” Like a very specific policy about documenting the identities of First Amendment auditors that apparently was sent out by the command through an email. So that’s the only reason that they’re a defendant there. And I think that’s really concerning if a city is potentially trying to develop a list of people who record police officers. Why? Why are they treating these people differently than the average person charged with a municipal offense?

FAW: Isn’t everyone who is arrested fingerprinted and photographed?

Schwab: I don’t know. I don’t know what that email looks like, but I have a comment from an officer saying, “Yeah, we got that email that said we don’t always have to fingerprint or take pictures, but for First Amendment auditors we do.”

FAW: In 2024, a federal judge upheld Cordova’s convictions for his recording inside an office of the U.S. Social Security Administration, for which his sentence included 15 days in jail, two years’ probation and a $3,000 fine. Is this a typical sentence?

Schwab: Honestly I was surprised. It’s a pretty harsh sentence. I was surprised at the moment that there was any jail time or any probation. Unfortunately, these types of probation sentences are sometimes kind of tilted towards trying to keep people in the system. You can [get] probation by showing up and trying to push the boundaries of the First Amendment, and that’s really unfortunate that good faith efforts to move the constitutional standards or constitutional rights can subject someone to jail time. It certainly does curtail his ability to continue to pursue this good, safe effort. [In this case], he reviewed the statute and it says “lobby” and “waiting rooms.” And the area he entered, and was arrested within 10 seconds of entering, wasn’t a waiting room. He had a good faith belief that this was a waiting room and that the law allows, federal regulations permit, filming, for news purposes, in a lobby. And there were people waiting in chairs. It wasn’t like he went to back offices. So it was a close call, I think, maybe the judge didn’t believe so, but I think it was a much closer call than it was portrayed.

FAW: Is the inside of the Social Security office considered a nonpublic forum?

Schwab: I would say it’s a non-public forum. It’s not a traditional public forum, and it wasn’t being held out for the purpose of speech. Now I would say that some First Amendment auditors, and I don’t want to speak for Chris here, believe that any public building should be accessible for the purpose of recording, at least the publicly available spaces like lobbies. I think that’s not an uncommon belief within the auditor community.

FAW: How would you compare Cordova’s recording inside a government building to recording police officers from a public sidewalk?

Schwab: From a First Amendment lens, you’re going to have a lot more protections in filming on the sidewalk. Assuming you don’t actually interfere with a police officer, generally, I would say that you should have essentially a nearly unlimited right to film.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include a statement from the Englewood Police Department.

More on First Amendment Watch: