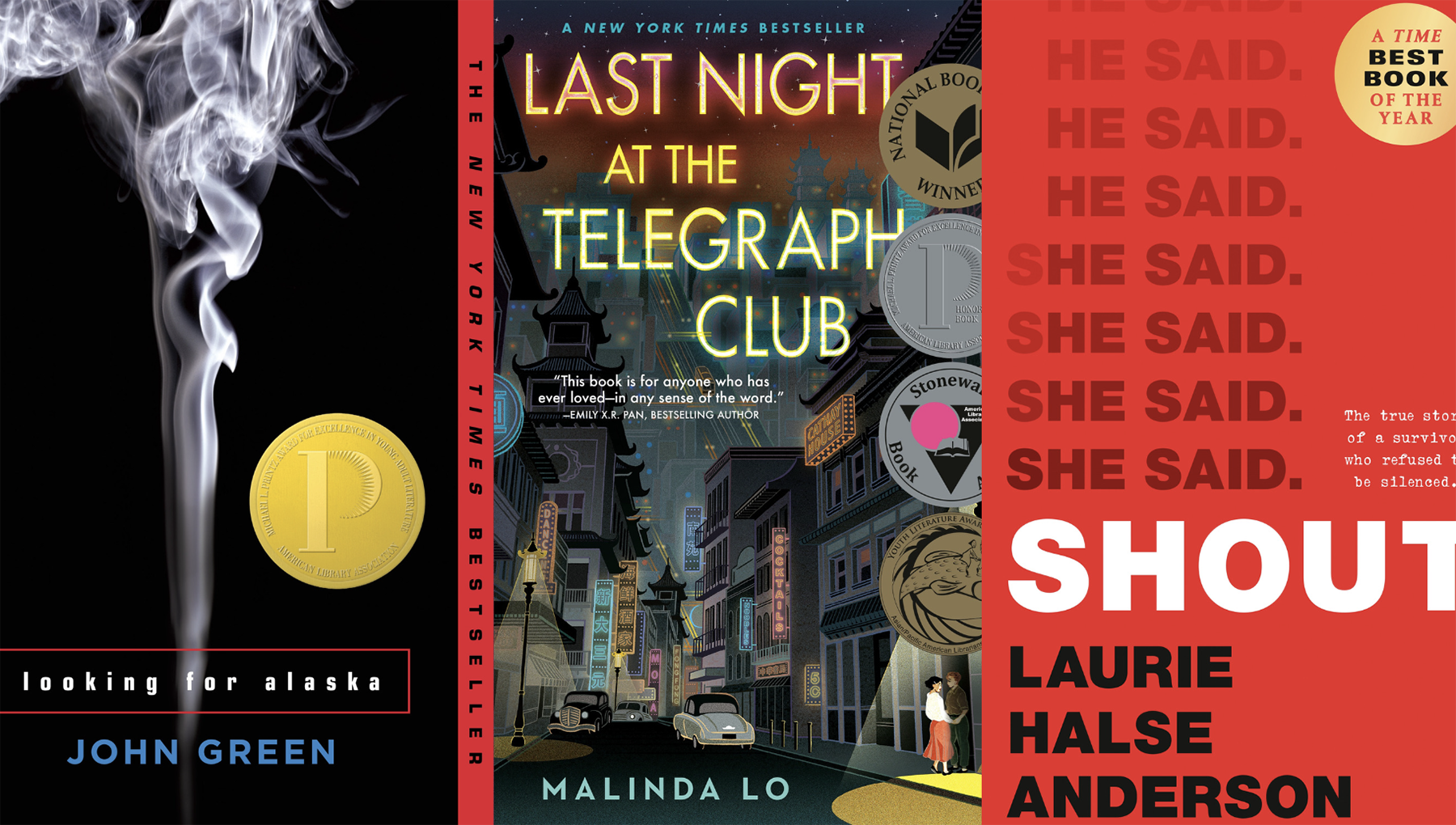

Best-selling author Laurie Halse Anderson, known for her young adult and children’s books, joined a lawsuit filed in November challenging a controversial Iowa law that allegedly prompted the recent removal of her 1999 breakout novel “Speak” from libraries and classrooms in 14 public school districts in the state.

“Speak” is based on Anderson’s personal experience with sexual assault as a teenager. The new Iowa law, Senate File 496, sought to ban books containing sexual content in public school libraries and classrooms through sixth grade, but parts of the law were temporarily blocked on Dec. 29, days before the law would have gone into effect.

Judge Stephen Locher of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Iowa said in his decision that the ban on books is “incredibly broad,” sweeping up award-wining novels and history books, and “even books designed to help students avoid being victimized by sexual assault.”

In an interview with First Amendment Watch, Anderson expressed concern about the new wave of book banning across the country and argued that parents, rather than shield their children from uncomfortable material, should use her book and others like it to have difficult conversations about important issues affecting their children’s lives.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.)

FAW: What sparked this lawsuit? And why did you sign on?

LHA: My books have been challenged many times over the years. “Speak” is commonly taught in high school, which comes as a surprise to some parents, so I’ve been used to talking to people about this, but it was evident very quickly that this was a new coordinated banning effort. So I was really heartened when Penguin joined with PEN America earlier this year in a lawsuit against Escambia County in Florida. And then they approached me about challenging one aspect of the Senate File 496 in Iowa, and I was immediately on board.

FAW: How is an author typically made aware that their book has been banned?

LHA: Sometimes it’s parents and teachers. But this is one of the challenges of living in a country as big as ours. It’s very hard to keep track of all these things. What’s difficult is that not all of the bannings are discussed publicly. In some states, this kind of work is going on very quietly, outside of the public view. And you find out, or I have found out, about some things long after the books were pulled from the shelves. So I think that when we’re looking at the statistics, it’s important to remember that there are no consistent requirements for reporting, and we’re not getting the entire picture.

FAW: Are you concerned, as an author, for the state of freedom of speech and expression in the United States?

LHA: I’m concerned as an author, but more importantly, I’m concerned as an American. I can’t say who these bans are aimed at, but I can say who they are affecting. They’re affecting all of our children, whether it’s books featuring characters or authors who are brown or Black, or characters or authors who are not cisgender or heterosexual. Those seem to be the people who are in the books that are being targeted the most. The result is bad for all of America’s children, because they are being deprived – and the families and the parents and the guardians of these kids are being deprived – of the opportunity to have access to a wide variety of books. Without access to a wide variety of books, you are limiting discussion, you are withholding knowledge, and you are damaging the growth not only of the next generation of kids, but the development of the country.

FAW: How so? What damage do you fear is being done?

LHA: I’m deeply, deeply worried that a small part of America’s population is trying to impose their worldview on the rest of us. And I get that democracy can be super uncomfortable, right? It’s not fun sometimes to have to operate in the world with people who think differently than you do. But that’s the only way that democracy succeeds. This has to be a foundational cultural touchstone for all of us, that we get to have the right to our own opinions. And that we have to agree that in the common spaces of our country, in the tax-funded spaces, that there is room and a celebration of a variety of people, of backgrounds, of opinions. And that’s the whole point of having public libraries and public education, is it creates those spaces where we get to learn together and respect our differences.

FAW: What would you say to parents who object to the content of your book?

LHA: One thing that I think has to be emphasized again and again, is that no child can be forced to read a book in this country. If there’s a book that a parent is uncomfortable with, or a child’s family says that ‘I don’t think my kid’s ready for that topic,’ in every single state I know of, there are mechanisms in place in the educational system, and the teachers are prepared for that. Because kids develop at different rates, and some kids have things in their backgrounds that might make reading a topic uncomfortable. No worries. We have always had the ability to give kids in that position a different book to read. It’s not a big deal. And so this notion that there are huge swaths of books, or huge topics of the human experience that should somehow be withheld from kids of all ages, because a small group of parents and politicians are uncomfortable with those topics, that just completely flies in the face of what this democracy is supposed to be built upon.

FAW: Sexual violence is a difficult topic. Why should we expose young people to it?

LHA: I would ask you to consider these reasons for young people to have access to books about sexual violence. Number one, sexual violence is one of the most frequent kinds of violence that children and teenagers experience. Number two, pretty much everybody who’s ever grown up to become sexually violent, nearly all those people at one point in life were sitting in a public school classroom. They were kids. We teach children in an age-appropriate, developmentally appropriate way, the dangers of a fire, the dangers of driving a car recklessly, the dangers of drug and alcohol abuse. We as a culture, as a community, consider that an important part of every person’s education. It’s health and safety. Understanding how sexual violence happens, why it happens, and how to prevent it from happening needs to be a part of all of those safety lessons. The only reason that we don’t have a consistent curriculum of consent-based healthy sexuality education in every single state is that there’s a whole lot of grownups in America who aren’t comfortable talking about sex. But in Iowa, if you’re 16 years old, you can give consent to have sex. In Iowa, if you’re 14 or 15 years old, you can give consent to have sex with somebody who’s no more than four years older than you. So clearly, the legislators of Iowa know that kids are having sex there. And that’s legal for some of them. But they’re afraid to have books about sex in the library. How does that make any sense?

FAW: Has anything about the public’s reaction to your work surprised you?

LHA: I visited thousands of high schools in the last 25 years. And I was baffled when I spoke to teenage boys, and they would say to me, “I didn’t get why the main character was so upset.” And that is the best question I’ve ever gotten in all of my years. Because these boys had the courage to be honest with me, because what their culture tells them about sexual violence was not what my book was saying. You have to understand that in America, according to the statistics I’ve read, a lot of, especially boys, are looking at violent pornography on their phones by the time they’re 11 and 12 years old. If that’s the only experience to human sexuality that they’re seeing, many of them grow up to believe that it’s supposed to be a violent act, and that’s just normal, and they’re never having responsible conversations with adults who point out not only the legal aspects of sexual harm and violence but the moral and ethical concerns. So your only understanding of human sexuality comes from watching violent porn on your phone? That’s why we need to have — in public spaces, public libraries, public education — access to a wide variety of books that are produced in a responsible way. These are books that are vetted before they get into a classroom or a library. They are reviewed by people who are experts in the development of children. They know what is age appropriate. There’s a lot of parents who want their children to have books that will explain these kinds of things, books that will help make the family conversations easier. I raised a bunch of teenagers. It’s a whole lot easier to talk to your kids about what’s going on in a book that you all read together. No parent wants to have this conversation. Humanity has always used stories to make these hard things easier, right? That’s what literature is for. We get to talk about the human experience in a way that opens our hearts and our minds.

More on First Amendment Watch