Pentagon Papers Whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg Dies at 92

Historic Articles and Interviews

June 13, 1971: Original New York Times Story on Pentagon Papers

The New York Times began publication of the documents, was barred by a court, and the mantle taken up by the Washington Post.

New York TimesJune 18, 1971: Original Washington Post Story on Pentagon Papers and Bradlee’s recollections

Washington Post headline June 18, 1971

Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee wrote it was difficult to get scooped by The Times on the Pentagon Papers which The Post did not yet have. But after The Times was restrained from publishing, The Post’s redoubled its efforts. Bradlee recalls, “The Post’s package consisted of something over 4,000 pages of Pentagon documents, compared with the 7,000 received by the New York Times. At 10:30 a.m. Thursday, June 17, Bagdikian rushed past Marina Bradlee, age 10, tending her lemonade stand outside our house in Georgetown, and we were back in business. For the next 12 hours, the Bradlee library on N Street served as a remote newsroom where editors and reporters started sorting, reading and annotating 4,000 pages, and the Bradlee living room served as a legal office where lawyers and newspaper executives started the most basic discussions about the duty and right of a newspaper to publish, and the government’s right to prevent that publication, on national security grounds, or on any grounds at all. For those 12 hours I went from one room to the other, getting a sense of the story in one place, and a sense of the mood of the lawyers in the other.”

Washington Post Washington PostJuly 1, 1971: Original New York Times Story on Supreme Court Decision in Pentagon Papers Case

A review of the 6-3 Supreme Court judgment that rejected prior restraint of publication.

May 11, 1973: Charges Dropped Against Ellsberg in Pentagon Papers Case

While The Times and The Post were allowed to continue their investigation into the Pentagon Papers but once outed, Daniel Ellsberg went on trial and was finally vindicated in May 1973.

New York TimesMay 29, 1997: Katharine Graham on the Pentagon Papers

Today: The Pentagon Papers and Press Freedom

May 16, 2017: Is It Ever OK For the Government To Ask Papers Not to Publish?

Callum Borchers looks at cases where the government and newspapers worked hand in hand to prevent sensitive national security information from being published.

Washington PostDecember 4, 2017: Daniel Ellsberg And The Necessity of Leakers

“I identify more with Chelsea Manning and with Edward Snowden than with any other people on Earth. They’re – we all come from very different backgrounds, different ages, different personalities, but we all faced the same question, which is who will put this information out if I don’t? And each of us came to the conclusion that this information that the public had to know would have to be put out by us, by ourselves, because no one else was going to do it,” said Ellsberg in an NPR interview.

January 2, 2018: The Guardian Looks at How Governments Continue to Toy with Press Freedom from The Post to Today

Peter Greste was arrested with two colleagues in Egypt in 2013 on terrorism charges, a crackdown on press freedom that he is reminded of by the new film, The Post, and the current state of journalism.

The GuardianJune 11, 2011: Why Full Disclosure is Best Way Forward

As the full archive of the Pentagon Papers went live, Daniel Ellsberg reflected on their meaning. “What we need released this month are the Pentagon Papers of Iraq and Afghanistan (and Pakistan, Yemen, and Libya). We’re not likely to get them; they probably don’t yet exist, at least in the useful form of the earlier ones. But the original studies on Vietnam are a surprisingly not-bad substitute, definitely worth learning from,” he wrote.

GuardianLooking Back: The Supreme Court’s Response

Rehnquist’s Phone Call to Bradlee: Cease Publication or Be Prosecuted Under Espionage Act!

Katharine Graham

The demand by the U.S. government that The Washington Post cease publishing its articles on the Pentagon Papers came soon after 3:00 p.m. on Friday, June 18, 1971. Benjamin Bradlee, managing editor of the Post, was in his office with publisher Katherine Graham and some editors when he took a call from Assistant Attorney General William H. Rehnquist (the following year, Rehnquist was appointed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and later Chief Justice).

Benjamin Bradlee

Rehnquist read the following statement to Bradlee, who wrote in his autobiography, A Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures, that after the call, “My hands and legs were shaking. The charge of espionage did not fit my vision of myself, and all I knew about Title 18 spelled trouble. That’s the Criminal Code.” The following is the demand that Rehnquist read to Bradlee:

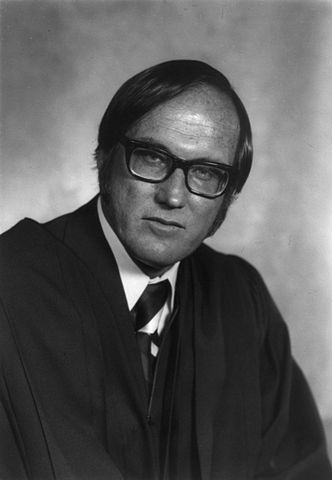

William Rehnquist Official 1972 Portrait

“I have been advised by the Secretary of Defense that the material published in The Washington Post on June 18, 1971, captioned ‘Documents Reveal U.S. Effort in ’54 to Delay Viet Election’ contains information relating to the national defense of the United States and bears a top-secret classification. As such, publication of this information is directly prohibited by the provisions of the Espionage Law, Title 18, U.S. Code, Section 793. Moreover, further publication of information of this character will cause irreparable injury to the defense interests of the United States. Accordingly, I respectfully request that you publish no further information of this character and advise me that you have made arrangements for the return of these documents to the Department of Defense.”

The Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court’s opinion in New York Times v. United States was a short three paragraphs with each justice weighing in separately.

“We granted certiorari in these cases in which the United States seeks to enjoin the New York Times and the Washington Post from publishing the contents of a classified study entitled “History of U.S. Decision-Making Process on Viet Nam Policy.” Post, pp. 942, 943.

“Any system of prior restraints of expression comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity.” Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 70 (1963); see also Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931). The Government “thus carries a heavy burden of showing justification for the imposition of such a restraint.” Organization for a Better Austin v. Keefe, 402 U.S. 415, 419 (1971). The District Court for the Southern District of New York, in the New York Times case, and the District Court for the District of Columbia and the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, in the Washington Post case, held that the Government had not met that burden. We agree.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit is therefore affirmed. The order of the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit is reversed, and the case is remanded with directions to enter a judgment affirming the judgment of the District Court for the Southern District of New York. The stays entered June 25, 1971, by the Court are vacated. The judgments shall issue forthwith.

So ordered...

The Archived Pentagon Papers

Links to the 48 boxes and approximately 7,000 declassified pages of information. Video is of U.S. Senator Mike Gravel reading the Pentagon Papers into the record in June 1971.

National Archives New York Times Washington PostHow the Nixon Administration Reacted

The Nixon Tapes

Tape recorder from President Nixon’s Oval Office

In February 1971, President Nixon began secretly taping conversations and telephone calls in several locations, including the Oval Office, his office in the Old Executive Office Building, the Cabinet Room, and Camp David. There are 2,636 hours of tapes containing conversations from February 1971 through July 1973 open to the public.

Listen to the conversations about how to silence reporters including the phone call between President Nixon and John Ehrlichman on Monday, June 14, 1971 at 7:13pm in which they discuss telling The New York Times not to run the story.

National ArchivesPrior Restraints—The Worst Form of Censorship

Prior restraints go back to 16th century England when the invention of the printing press made it possible to spread dissent and new ideas widely. Such publications could pose a threat to the Crown or accepted religious doctrine, so Henry VIII instituted a system of licensing printers and official censorship to control the spread of ideas. The licensing and censorship system expired in 1694 and in the colonies a few decades later, leaving post-publication punishment through seditious libel laws (criminal offense of criticizing government or public officials) the most effective way to punish dissent.

Sir William Blackstone

The lapsing of licensing and censorship before publication became central to the definition of a free press in English common law, which was adopted in the American colonies. In his Commentaries on the Laws of England, 1765-1769, William Blackstone defined freedom of the press as the absence of prior restraints. “The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state: but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public: to forbid this, is to destroy the freedom of the press: but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequence of his own temerity. To subject the press to the restrictive power of a licenser, as was formerly done, both before and since the revolution, is to subject all freedom of sentiment to the prejudices of one man, and make him the arbitrary and infallible judge of all controverted points in learning, religion, and government.”

Given this history, the First Amendment has always been seen as providing, at a very minimum, freedom from these “previous restraints upon publications.” Except in rare circumstances, the First Amendment prevents censorship by the government or by a private party acting through an injunction issued by a judge.

But even the doctrine of prior restraints has some exceptions. Two key Supreme Court decisions lay out the parameters of the law. In Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931), the Court said that the government might be able to procure a prior restraint in cases involving “actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of the sailing dates of transports or the number and location of troops,” a kind of national security exception. It also listed obscene publications, incitements to acts of violence, and speech directed to the overthrow of the government.

Daniel Ellsberg

The most famous prior restraint case is New York Times v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971). The Nixon Administration sought to stop the Times and The Washington Post from publishing stories from leaked classified documents called the Pentagon Papers, a Department of Defense study of U.S. decision-making before and during the conflict in Vietnam. Daniel Ellsberg, a consultant who had worked on the 7,000-page study, leaked it to the newspapers. A federal appeals court in Washington, D.C. upheld the right of The Washington Post to publish its stories on the Pentagon Papers, but the federal appeals court in New York issued an injunction against The New York Times. The two cases were combined at the Supreme Court. From beginning to end, the case sprinted to a decision in just 16 days, a mark of its importance since a newspaper had been stopped from publishing stories of enormous public interest.

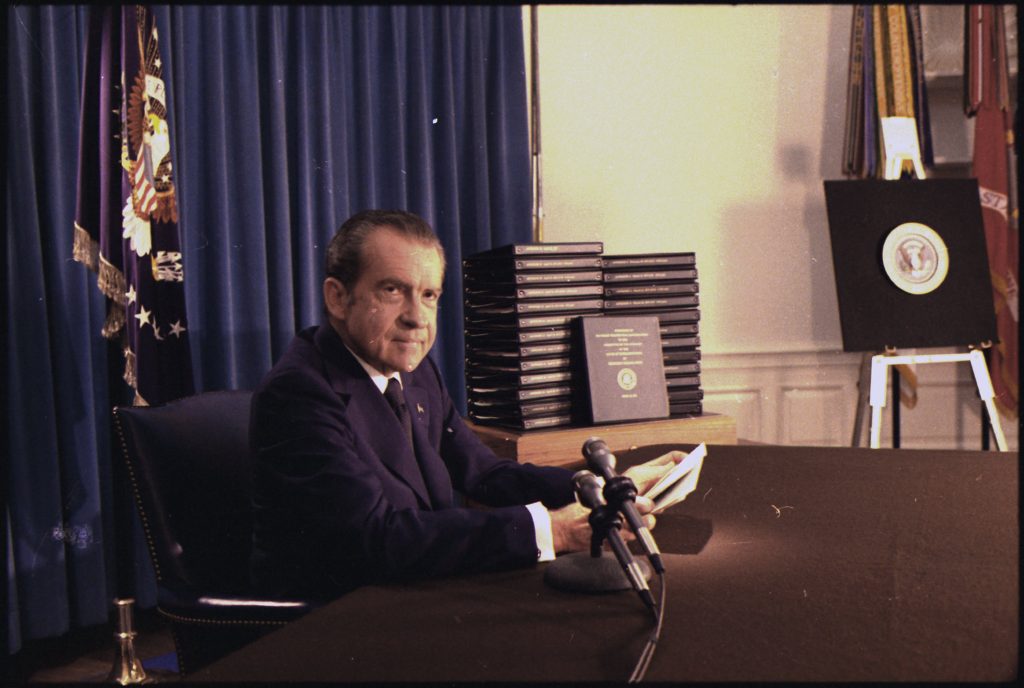

Nixon Press Conference Releasing White House Transcripts

The Supreme Court ruled 6 to 3 to lift an injunction against the Times. In a three-paragraph per curiam opinion, it said that any request for a prior restraint “comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity.” The government, the Court said, had not met its burden of showing justification for a restraint on publication. The Court did not articulate a test that the government would have to satisfy in order to stop publication, but Justice Potter Stewart in a concurring opinion stated that publication of information would have to “surely result in direct, immediate, and irreparable damage to our Nation and its people.” Federal courts have utilized Stewart’s test—an exceptionally difficult standard to meet—in later cases. Whether it is the government or a private party asking for a prior restraint, the focus is on the likelihood that publication would cause serious and imminent harm.

New York Times v. United States

What the movie “The Post” Gets Right—and Gets Wrong

December 22, 2017: “Hollywoodization” of Pentagon Papers Stretches The Truth

The lead attorney for The New York Times writes that “The Post” is “a good movie but bad history.” He points out that a federal appeals court stopped The Times from publishing its series on the Pentagon Papers before The Washington Post even received the documents from Daniel Ellsberg. “The risk assumed by the Times was not insubstantial,” James Goodale wrote in the Daily Beast. If the documents turned out to be fake, the Times would have great difficulty recovering institutionally. If the Times’ legal advice was wrong and the paper was convicted of a crime, its loss of reputation would be irretrievable”

Daily BeastDecember 15, 2017: Cast of ‘The Post’ Reflects On Pentagon Papers And Relevance Today

Washington PostMarch 4, 2018: “The Post” Misses an Important Piece About The New York Times’ Role

The movie,”The Post,” was missing an important piece about The New York Times’ involvement in the Pentagon Papers story argues Kevin Lerner in The Washington Post. “In short, the publication of the Pentagon Papers was a culmination of journalistic work and legal battles the Times had launched a decade earlier — an important complexity of the real world of journalism that the movie “The Post” ignores.”

The Washington PostAdditional Resources

Documentary on Pentagon Papers and Freedom of the Press

In this documentary, a group of writers and scholars, including the First Amendment Watch’s founding editor, Stephen D. Solomon, examine the First Amendment’s protection of a free press as well as the historic origins of this right and the ramifications of the landmark ruling in New York Times v. United States, the Pentagon Papers case, in which the Supreme Court ruled that prior restraint is unconstitutional.

Retrospect: Erwin Griswold—Pentagon Papers Did Not Pose a Threat to National Security

Erwin Griswold

Erwin Griswold, the Solicitor General of the United States, argued the government’s case before the Supreme Court in 1971. He failed to convince the justices that publication of the Pentagon Papers constituted an irreparable threat to the country. Eighteen years later, he wrote in The Washington Post that in hindsight the Papers had not affected U.S. security at all. “I have never seen any trace of a threat to the national security from the publication,” Griswold wrote in 1989. “Indeed, I have never seen it even suggested that there was such an actual threat.” He continued: “It quickly becomes apparent to any person who has considerable experience with classified material that there is massive overclassification and that the principal concern of the classifiers is not with national security, but rather with governmental embarrassment of one sort or another. There may be some basis for short-term classification while plans are being made, or negotiations are going on, but apart from details of weapons systems, there is very rarely any real risk to current national security from the publication of facts relating to transactions in the past, even the fairly recent past. This is the lesson of the Pentagon Papers experience, and it may be relevant now.”

Floyd Abrams on The Enduring Impact of the Pentagon Papers

Read an interactive oral history of the Pentagon Papers published by The New York Times

In celebration of the 50 year anniversary of the Pentagon Papers, the New York Times published a compilation of interviews with the reporters, editors, and researchers who helped prepare the series.

Read an interactive oral history of the Pentagon Papers published by The New York Times

In celebration of the 50 year anniversary of the Pentagon Papers, the New York Times published a compilation of interviews with the reporters, editors, and researchers who helped prepare the series.